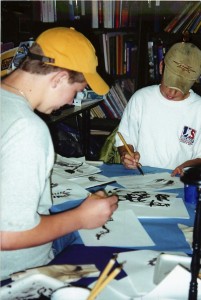

Two seventh-grade boys with baseball caps on are seriously engaged in Chinese brush painting in their Language Arts class. Their caps are well worn, fit snugly on their heads, and the bills are curved just right. The students are not speaking but are examining their pictures with heads bent while adding more brush strokes of black paint on the white paper. Their faces are relaxed and other paintings are lying around—previous attempts using the brush technique they have just learned. One boy is painting a dragon, the other a landscape. The paintings are simple, stark, and expressive.

Two seventh-grade boys with baseball caps on are seriously engaged in Chinese brush painting in their Language Arts class. Their caps are well worn, fit snugly on their heads, and the bills are curved just right. The students are not speaking but are examining their pictures with heads bent while adding more brush strokes of black paint on the white paper. Their faces are relaxed and other paintings are lying around—previous attempts using the brush technique they have just learned. One boy is painting a dragon, the other a landscape. The paintings are simple, stark, and expressive.

I take many pictures of students every year, and I as rifled through them, this is the first one I came to that said something important about teaching to me. It said, this was one of your better lessons, this was one of those lessons that felt satisfying both while doing it and on reflection as well. It was a lesson that would become a permanent part of my teaching repertoire. Why?

Art is an effective and wonderful teaching method. Art is powerful: it can disarm the scared, the cautious, or the suspicious; it can lead to a rewarding product; it encourages creativity; it is expressive; it explores concepts of beauty; it reinforces concepts that integrate disciplines such as balance, focus, pattern, and rhythm.

This picture shows, for example, that two athletic, “tough” boys are being quiet, creative, expressive and are learning how to do something new with brushes and are fascinated with the whole idea. These are two boys who are not usually thrilled about writing in language arts, but they will be enticed into the idea of writing haiku by being allowed to paint a picture to go along with it. I demonstrate a painting stroke technique that tends to make realistic images without a lot of artistic skill. Everyone can be and needs to be expressive, but sometimes students don’t know what to write about, or where to start. For those, this lesson works especially well: they paint a picture after watching me demonstrate, and then they have something lovely (or at least interesting or original) to write about. Almost everyone is happy with the results.

If I look deeper into the photograph for something about teaching, I see individuals working on individual products after being given instruction as a whole group on possible ways of doing something. They watched me model the technique and have been warned about some things that will cause problems if they are not careful. Students are excited about trying. They are deep in thought as they do it. Results are shared; they talk about them and laugh, and learn from others. They are challenged each at his or her own level. There are models to copy for those who “don’t know what to paint” and those who do know are dying to experiment and try something on their own. They are intrigued by doing something fun in language arts, something different. They can be serious or lighthearted in what they choose to paint.

It is interesting that as I looked deeper into the picture, what suddenly stood out was that these boys (and the whole class that day) were doing individual work that was naturally differentiated. Having been encouraged lately by administrators and current trends in education to use more group differentiation in designing lessons led me to consider whether a more natural approach to differentiation wasn’t possible and preferable.

When does group differentiation by ability lead to individuals learning more than they would in whole class or individual methods of instruction? This is an important question to ask today’s educators. Many teachers, for instance, go to great lengths to make three levels of tests, three different projects or assignments, in addition to differentiated group class work. I have seen teachers in the hall with their “gifted ” group, giving them instructions on what to do as they trot off to the library, but I can’t help but wonder what the rest of the students in the class are thinking about why they aren’t in that group. It is often assumed that the more differentiation a teacher does by ability, the better.

Group work is essential and valuable and “the best practice” for certain kinds of lessons. I find it useful, for example, when I teach the parts of speech and tell the students to be language scientists and sort words together and be as creative as they want in how they categorize the words. I want them to talk and solve the problems that come up jointly. If they did this individually, some would not bother to try, some would not know where to begin, and they wouldn’t be exposed to all the possibilities for organization and problems that a group of kids will come up with and solve together. The group pulls in the reluctant learners because so many kids are excited about seeing if they can do it, some think they already know all the answers and will run into problems with which others will have to help them. Groups are useful when there is a collaborative job to be done that requires or encourages different types of approach. In this parts of speech activity, groups are not formed by ability, however; they are heterogeneous. It takes different perspectives working together to discover the complexities and possibilities of creative sorting.

Should I use ability groupings for the haiku painting activity? I think not, even though some students will be much better at it and quicker to learn it than others. Why not? Better students could help less able students, for one thing, so I wouldn’t want them separated. One of the nice things about this activity is that kids can sit with their friends (for once) if they want. It is so engaging that a seating chart isn’t necessary to help keep them on task. It is a naturally differentiating activity and setting: kids watch and help each other, they roam around the room looking at each other’s work and asking questions.

One lesson I have used ability grouping for is when we do peer edit groups. In the writing groups, I tell students that I am grouping them according to where they have demonstrated strengths and I then give all the groups positive labels: the “Punctuation Prefects,” the “Word Wizards,” the “Sentence Sentinels,” etc. Since they will be editing others’ papers, it is important to have them at tables where they can help the writer. Even the least talented writers can edit for margins and spacing errors; they are the “Form Finders.” No one is therefore demeaned by the differentiated groupings.

Pigeon-holing students and then trying to conceal why they are grouped a certain way, on the other hand, is not an effective or encouraging way to differentiate by ability. One administrator suggested, for example, that my literature unit should be structured with a warm-up, a whole class review, and then group work where students completed folder work based on ability. Red folders would have picture book work, yellow folders for Amelia Bedelia, and green folders for Incredible Journey, but all would have some analysis questions about literature.

I don’t think such a method is pedagogically sound for a number of reasons: 1. Who will keep all groups on task (especially the group with the picture book, who may feel demeaned by the activity)? 2. Will the teacher be able to help all groups in a meaningful way during one class period? 3. It is a huge amount of preparation for the teacher. Do the results justify it? 4. Why are children all in the same class if ability groupings really work better? 5. How do the students feel about being told in what group they “belong” ? And there’s the rub for me: labels are being put on students that may inhibit potential and performance, to say nothing of what they may do to a student’s motivation or self-esteem.

Labels are a necessity of life, but perhaps some are more detrimental than others and certainly we should be most careful about how we use them in education. Consider “learning disabled,” and “gifted” for two. Surely all of us have gifts and surely being told you are disabled is anything but encouraging. Then there is the type of labeling that goes on that doesn’t have a specific name, but has a specific expectation: when a teacher gives one group of students a red folder of work and gives another group of students a yellow folder of work, or when a teacher gives out three different tests on the material in the class. Some teachers, in addition, go to extreme lengths to conceal that we are telling students that in our eyes they are not the same in ability and we do not expect the same things from them. Maybe I am getting old, but I don’t think my eyes are so good that I can see every bit of potential inside all of my students.

Part of the marvelous nature of being human is that we are capable of all sorts of wonders and surprises. Who are we as humans to judge how far others can go on a given task or how much they will strive to learn? Such behavior robs students of their dignity in taking away their own freedom to make their own decisions about how hard they can work or how much they can learn. One of the interesting things I witness in Language Arts every year is that the student who hates writing may be the star of the class play. A student who was tortured by having to write a short story could shine when we wrote essays. The student who can ace the weekly vocabulary tests may be a poor reader compared to others in the class. People also change. A poor student may decide to put more effort into something now and then, just as a good student may become too busy, overwhelmed, or depressed and not want to take on the more challenging work.

Obviously expectations that are too high can be daunting as well. I think that there are natural ways of differentiating that do not inhibit or demean students and that allow students the freedom to choose how high they will fly and also invites them all to work at the highest possible level. If a unit is planned well, it can not only challenge all students where they are, but it can at the same time respect the self esteem and autonomy of the individual by avoiding labeling and assumptions about students’ abilities. The Chinese painting activity is one such example.

But not only art activities lend themselves to natural differentiation; I have used the same approach with my vocabulary unit on word stems. All students can learn a list of ten word stems with one-word definitions, which forms the basic content of each week’s lesson. Students are then given worksheets with questions designed to challenge the spectrum of abilities. Since we go over their answers in class, students are naturally motivated to find something to share and tend to stretch to their individual level in so doing. There are some easier activities, such as underlining each word that uses one of the stems, and then some harder ones, such as “Given that extra means beyond and terre means earth, what is something that might be considered extraterrestrial?”

We then review for the cumulative tests by playing vocabulary baseball, a tried and true natural motivator. Students come to bat and have to ask for a single (one word stem), a double (two word stems), a triple (three word stems) or a homerun (four word stems); but there are many other ways to add challenges to the activity so students can opt for varying amounts of challenge when they come to bat. Teachers can also allow students who need more repetition of the material to be the pitcher, thus reinforcing seeing the stems and their definitions over and over while including everyone in the game.

Isn’t it theoretically possible to plan all units/activities this way? And doesn’t this way respect the autonomy, self-esteem, and motivation of the student in a way that red and yellow folders cannot?

1 Comment